Valley Fever – Coccidiodomycosis

Definition

Valley fever is caused by fungi in the soil. The fungi that cause valley fever can be stirred into the air by anything that disrupts the soil, such as farming, construction and wind. The fungi can then be breathed into the lungs. Valley fever is a form of coccidioidomycosis (kok-sid-e-oi-doh-mi-KOH-sis), or cocci (KOK-si) infection. It can cause fever, chest pain and coughing, among other signs and symptoms.

More than half of those who inhale the valley fever fungi have few, if any, problems. But some, especially pregnant women, people with weakened immune systems, and those of Asian, Hispanic and African descent, may develop a more serious and sometimes fatal form of coccidioidomycosis infection.

Mild cases of valley fever usually go away on their own. In more severe coccidioidomycosis infections, doctors prescribe antifungal medications that can treat the underlying infection.

Symptoms

Valley fever is one of three forms of coccidioidomycosis. The forms include: acute (valley fever), chronic, and disseminated.

Acute coccidioidomycosis (valley fever)

The acute form is often mild, with few, if any, symptoms. When signs and symptoms do occur, they appear one to three weeks after exposure. They tend to resemble those of the flu, and can range from minor to severe:

Fever

Cough

Chest pain — varying from a mild feeling of constriction to intense pressure resembling a heart attack

Chills

Night sweats

Headache

Fatigue

Shortness of breath

Joint aches

Red, spotty rash

The rash that sometimes accompanies valley fever is made up of painful red bumps that may later turn brown. The rash mainly appears on your lower legs but sometimes on your chest, arms and back. Others may have a raised red rash with blisters or eruptions that look like pimples.

If you don’t become ill from valley fever, you may only learn that you’ve been infected when you later have a positive skin or blood test. Small areas of residual infection (nodules) in the lungs that show up on a routine chest X-ray may also be found. Although the nodules typically don’t cause problems, they can look like cancer on X-ray, leading to biopsies.

If you do develop symptoms, especially severe ones, the course of the disease is highly variable. It can take from six months to a year to fully recover, and fatigue and joint aches can last even longer. The severity of the disease depends on several factors, including your overall health and the number of fungus spores you inhale.

Chronic coccidioidomycosis

Appearing as many as 20 years after the initial infection, chronic pneumonia due to coccidioidomycosis is most common in people with diabetes or weakened immune systems. You’re likely to have periods of worsening symptoms alternating with periods of recovery. Signs and symptoms are similar to those of tuberculosis:

Low-grade fever

Weight loss

Cough

Chest pain

Blood-tinged sputum

Nodules in the lungs

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis

The most serious form of the disease, disseminated coccidioidomycosis occurs when the infection spreads (disseminates) beyond the lungs to other parts of the body. Most often these parts include the skin, bones, liver, brain, heart, and the membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord (meninges).

The signs and symptoms of disseminated disease depend on which parts of your body are affected and may include:

Nodules, ulcers and skin lesions that are more serious than the rash that sometimes occurs with other forms of the disease

Painful lesions in the skull, spine or other bones

Painful, swollen joints, especially in the knees or ankles

Meningitis — an infection of the membranes and fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord and the most deadly complication of valley fever

Causes

The fungi that cause valley fever — Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii — thrive in the alkaline desert soils of southern Arizona, northern Mexico and California’s San Joaquin Valley. They’re also endemic to New Mexico, Texas and parts of Central and South America — areas with mild winters and arid summers.

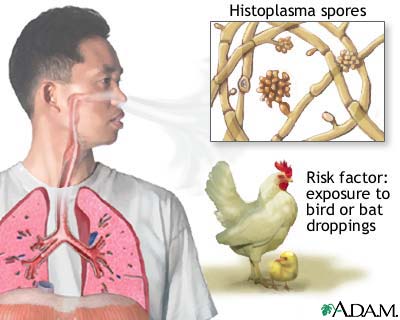

Like many other fungi, coccidioides species have a complex life cycle. In the soil, they grow as a mold with long filaments that break off into airborne spores when the soil is disturbed. The spores are extremely small, can be carried hundreds of miles by the wind and are highly contagious. Once inside the lungs, the spores reproduce, perpetuating the cycle of the disease.

Risk factors

Environmental exposure. Anyone who inhales the spores that cause valley fever is at risk of infection. Some experts estimate that up to half the people living in areas where valley fever is common have had the disease. People who have jobs that expose them to dust are most at risk — construction, road and agricultural workers, ranchers, archeologists, and military personnel on field exercises.

Smoking. Smokers, especially those with scarring and thickening of lung tissue (pulmonary fibrosis), are at higher risk of valley fever and subsequent chronic pneumonia than are nonsmokers.

Race. For reasons that aren’t well understood, Filipinos, Hispanics, blacks and Asians are more susceptible to developing serious infection with coccidioidomycosis than are whites.

Pregnancy. Pregnant women are vulnerable to more serious coccidioidomycosis in the third trimester and right after their babies are born.

Diabetes. Valley fever infection may be more severe among people with diabetes.

Weakened immune system. Anyone with a weakened immune system is at increased risk of serious complications, including disseminated disease. This includes people living with AIDS or those being treated with steroids, chemotherapy or anti-rejection drugs after transplant surgery. People with cancer and Hodgkin’s disease also have an increased risk.

Age. Older adults are more likely to develop valley fever than younger people are. This may be because their immune systems are less robust or because they have other medical conditions that affect their overall health.

When to seek medical advice

Valley fever, even when it’s symptomatic, often clears on its own. Yet for older adults and others at high risk, recovery can be slow and the risk of disseminated disease high. For that reason, it’s important to seek medical care if you develop the signs and symptoms of valley fever, especially if you live in or have recently traveled to an area where this disease is common.

Be sure to tell your doctor if you’ve traveled to a place where valley fever is endemic and have symptoms. More and more, people who spend a few days golfing or hiking in Arizona return home with valley fever but are never tested for the disease.

Tests and diagnosis

Valley fever isn’t diagnosed on the basis of signs and symptoms, which are usually vague and nonspecific, or on a chest X-ray, which can’t distinguish valley fever from other lung diseases. Instead, a definitive diagnosis depends on finding Coccidioides spherules (cysts) in tissue, blood or other body secretions. For that reason, you’re likely to have one or more of the following tests:

Sputum smear or culture. These tests check a sample of your sputum for the presence of the valley fever fungus.

Blood tests. Through a blood test, your doctor can check for antibodies against the fungus that causes valley fever.

Complications

Valley fever can cause a number of serious complications, especially in people living with HIV/AIDS.

These complications include:

Severe pneumonia. Most people recover from valley fever pneumonia without complications. Others, mainly Filipinos, Hispanics, blacks and Asians and those with weakened immune systems, may become seriously ill.

Ruptured lung nodules. A small percentage of people develop thin-walled nodules (cavities) in their lungs. Many of these eventually disappear without causing any problems, but some may rupture, causing chest pain and difficulty breathing. A ruptured lung nodule might require the placement of a tube into the space around the lungs to remove the air, or surgery to repair the damage.

Disseminated disease. This is the most serious complication of coccidioidomycosis. If the fungus spreads (disseminates) throughout the body, it can cause problems ranging from skin ulcers and abscesses to bone lesions, severe joint pain, heart inflammation, urinary tract problems and meningitis — an infection of the membranes and fluid covering the brain and spinal cord.

Treatments and drugs

Rest often the only treatment

Most people with acute valley fever don’t require treatment. Even when symptoms are severe, the best therapy for otherwise healthy adults is often bed rest and fluids — the same approach used for colds and the flu. Still, doctors carefully monitor people with valley fever.

Antifungal medications

If symptoms don’t improve or become worse, or if you are at increased risk of complications, your doctor may prescribe an antifungal medication such as fluconazole. Antifungal medications are also used for high-risk people or for those with chronic or disseminated disease.

In general, the antifungal drugs fluconazole and itraconazole are used for all but the most serious cases. All antifungals can have serious side effects. However, these side effects usually go away once the medication is stopped. The most common side effects of fluconazole and itraconazole are nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea. More serious infection may be treated initially with an intravenous antifungal medication such as amphotericin.

These medications control the fungus but sometimes don’t destroy it, and relapses may occur. For many people, a single bout of valley fever results in lifelong immunity, but the disease can be reactivated or you can be reinfected if your immune system is significantly weakened.

Prevention

If you live in or visit areas where valley fever is common, take common-sense precautions, especially during the summer months when the chance of infection is highest. Consider wearing a mask, staying inside during dust storms, wetting the soil before digging, and keeping doors and windows tightly closed.

Valley Fever or Coccidioidomycosis

The technical name for Valley Fever is Coccidioidomycosis, or “Cocci” for short. It is caused by Coddidioides immitis, a fungus somewhat like yeast or mildew which lives in the soil. The tiny seeds, or spores, become wind-borne and are inhaled into the lungs, where the infection starts. Valley Fever is not contagious from person to person. It appears that after one exposure, the body develops immunity.

Valley Fever is a sickness of degree. About 60 percent of the people who breathe the spores do not get sick at all. For some, it may feel like a cold or flu. For those sick enough to go to the doctor, it can be serious, with pneumonia-like symtoms, requiring medication and bed rest.

Of all the people infected with Valley Fever, one or more out of 200 will develop the disseminated form, which is devastating, and can be fatal. These are the cases in which the disease spreads beyond the lungs through the bloodstream – typically to the skin, bones, and the membranes surrounding the brain, causing meningitis.

If you live in an endemic area, you may have had Valley Fever without even knowing it. In some endemic areas, it is estimated that as much as half of the population has been infected. Persons whose activities put them in much contact with the soil appear to have a somewhat greater risk. Once infected, persons of African, Filipino and some other Asian ancestries seem to be at a greater risk of contracting the more serious, or disseminated, form of the disease. The young, the old, and those with lowered immune systems are also in the high risk group. While men are at greater risk than women, pregnant women are especially vulnerable, particularly in the third trimester.

Diagnosis

Usually, diagnosis is made on the basis of one or more of the following three tests: recovery of the Cocci organisms from sputum or some other body fluid; blood tests that reflect the body’s reaction to the presence of the fungus; and skin tests. These tests are quite reliable, but they may fluctuate according to the stage of the disease. Chest X-rays reveal some of the abnormalities associated with Cocci, but the shadows are difficult to distinguish from those of tuberculosis or some other lung disease.

Treatment

Patients suffering from the flu-like symptoms of Cocci will probably be sent to bed by the doctor. Since most cases are mild and self-limiting, there is no consensus on how aggressively it should be treated. However, once serious symptoms appear – including pneumonia and labored breathing – treatment should be prompt. Unfortunately, all four antifungal drugs in use are disagreeable and often toxic. Although it is the “gold standard” of treatment, Amphotericin B is the worst, according to patients, especially to those who have to have it injected beneath the base of their skull for meningitis. Its side effects include nausea, fever and kidney damage. Oral drugs include ketoconazole and more recently, fluconazole and itraconazole.

In severe cases, where the fungus has permanently damaged lung or bone tissue, surgery may be needed. Since the drugs serve only to suppress the fungus, not to kill it, those who develop a severe case of Valley Fever may require treatment for years.